Diagnosing PSEUDOBULBAR AFFECT (PBA)

Based on data from 2011, many patients with Pseudobulbar Affect (PBA) may remain undiagnosed17

For patients with complex neurologic conditions and comorbid mood or behavioral disorders, crying and other outbursts can be common. This can make your evaluation of their symptoms challenging. But getting to the right diagnosis is crucial to reducing the impact of PBA episodes on your patients’ lives.

DO YOU KNOW THE SYMPTOMS OF PBA?

Screening for PBA, or following the steps below, can make all the difference. PBA is a distinct, treatable condition, but it can only be treated with the correct diagnosis.

According to a 2011 online survey of patients and caregivers that was used to estimate the prevalence of PBA in the United States (N=2,318), of the 937 respondents who screened positive for PBA symptoms:17

73.6% (637)

talked to their doctor about their episodes.

41% of those that spoke to their doctor (227)

were given a diagnosis.

None (0)

of the reported diagnoses were for PBA.

a A positive screening for PBA was determined by a Center for Neurologic Study-Lability (CNS-LS) score of 13 or greater and/or a report of sudden laughing and/or crying episodes. The CNS-LS is a seven-item self-report rating scale that measures perceived frequency and control over laughing and/or crying episodes. It was validated as a PBA screening tool in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and multiple sclerosis (MS) populations. Higher CNS-LS scores are indicative of more frequent uncontrollable laughing and/or crying episodes. This scale does not confer a PBA diagnosis.18,19

A proper PBA diagnosis starts with you

PBA occurs secondary to certain neurologic conditions or brain injuries. It is also often comorbid with depression and/or other mood and behavioral disorders. PBA is distinct from other forms of mood, affective, or emotional lability. If your patients with a neurologic condition or brain injury who have been diagnosed with and treated for depression are still experiencing involuntary, sudden, frequent laughing and/or crying episodes, it could be time to screen for PBA.1-4

Also, keep in mind that PBA episodes may not appear when the patient is with their doctor, so asking the right questions of your patients, their caregivers, and your medical team is important for reaching an accurate diagnosis.

Three steps to PBA diagnosis

To start your evaluation, you need to know the symptoms of the condition and the criteria against which to judge.

It can also be helpful to ASK your patients and their caregivers:

Can you tell me about any changes in your laughing and/or crying since your stroke diagnosis?

If laughing and/or crying episodes are impacting your patient, take these three steps.

1

CONFIRM if there is an underlying neurologic condition or brain injury—including but not limited to:1,4,5

- Stroke

- Traumatic brain injury (TBI)

- Multiple sclerosis (MS)

- Dementia/Alzheimer's disease

- Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)

- Parkinson's disease

Common comorbidities and other considerations

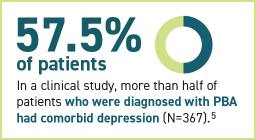

Mood disorders or behavior changes commonly co-occur with many underlying neurologic conditions. As such, while a mood-related condition is not required for a PBA diagnosis, PBA is often comorbid with mood and behavioral disorders.

When exploring a PBA diagnosis, it can also help to review your patient's chart for:

History of any mood-related conditions with which the underlying condition may co-occur: 3, 20, 21

- Depression

- Delusions

- Aggression

- Personality changes

- Anxiety

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

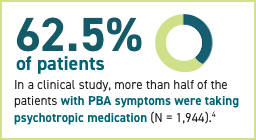

Current list of medications, such as those taken to treat mood or behavioral disorders:

- Antidepressants

- Anxiolytics

- Antipsychotics

- Sedatives and hypnotics

- Psychostimulants

- Anticonvulsants

2

DETERMINE if their laughing and/or crying symptoms and presentation suggest PBA. Patients may describe their uncontrollable laughing and/or crying episodes in different ways.6,7

Some of the hallmarks of Pseudobulbar Affect episodes include:1,3-6,8

INVOLUNTARY

It happens in public. I can’t control it.

SUDDEN

I cry for no reason. It comes out of the blue.

FREQUENT

I cry more than I used to. The littlest thing sets me off.

PBA episodes can also be exaggerated and/or incongruent.6, 8, 9, 11-13

EXAGGERATED

Excessive or disproportionate in relation to mood or stimulus.3 Patients may experience variability in the initiation, duration, and intensity of their laughing and/or crying episodes.

I overreact to things now.

Laughing and/or crying episodes are excessive but consistent with stimulus and feelings.8

I can’t stop myself from crying.

Laughing and/or crying episodes are sudden, uncontrollable, and may be stronger than normal reactions.6,8

INCONGRUENT

Inappropriate or inconsistent in relation to mood or stimulus.6 Episodes may not follow a stereotyped pattern in terms of length and severity, and expression of laughing and/or crying.6,8

I don’t know why I am crying.

Laughing and/or crying episodes don’t match feelings, and there may be no meaningful stimulus.8

It comes out of nowhere.

Laughing and/or crying episodes are sudden, uncontrollable, and may be brief (seconds or minutes).6,8

PBA involves a disconnect between:6,14

Affect

Expression of emotion

Mood

Underlying emotional state

In PBA, crying may be indistinguishable from normal crying.6, 8-10

Click on the navigation on the right to view examples of PBA crying episodes.

Appears with or without tears

Tears may or may not be present when crying.

In PBA, crying may:

- Appear with or without tears

- Sound noiseless or quiet

- Sound noisy with increasing volume

- Appear with or without grimacing

Download transcripts of these videos.

Nurses and other staff members may also describe your patient’s symptoms in different ways. Look for some of these terms on patient charts that may suggest PBA: 1,14

- Emotional incontinence

- Emotional lability

- Inappropriate affect

- Involuntary expression

- Mood incongruence

- Pathological laughing and crying

- Sudden or emotional outbursts of laughing or crying

3

DOCUMENT your diagnosis

Once you've confirmed your diagnosis, you can document it with ICD-10 code F48.2.15

PBA is treatable with NUEDEXTA — the first and only FDA-approved treatment for PBA.16

Are you a healthcare provider working in the long-term care setting?